During the age of discovery and afterwards European explorers all over the world sent back travelogs recording their adventures in foreign and exotic lands. Some of them were perhaps not as…accurate as the public came to believe. But the more sensational they were, the better they sold. There were tales of living dinosaurs in Africa, crystal skulls in central America, and even 62 ft. anacondas swimming the rivers of the Amazon.

And in 1873 the New York World published a thrilling account of a German botanist and explorer named Karl Leche. Karl had traveled to Madagascar and encountered a remote and primitive tribe called the Mkodo. The Mkodo, he found, had a rite of human sacrifice centering around enormous plants that he dubbed Crinoida dajeeana ‘the Man-eating tree of Madagascar’:

“If you can imagine a pineapple eight feet high and thick in proportion resting upon its base and denuded of leaves, you will have a good idea of the trunk of the tree, a dark dingy brown, and apparently as hard as iron. From the apex of this truncated cone eight leaves hung sheer to the ground. These leaves were about 11 or 12 ft long, tapering to a sharp point that looked like a cow’s horn, and with a concave face thickly set with strong thorny hooks. The apex of the cone was a round white concave figure like a smaller plate set within a larger one. This was not a flower but a receptacle, and there exuded into it a clear treacly liquid, honey sweet, and possessed of violent intoxicating and soporific properties. From underneath the rim of the undermost plate a series of long hairy green tendrils stretched out in every direction. These were 7 or 8 ft long. Above these, six white almost transparent palpi [tentacles] reared themselves toward the sky, twirling and twisting with a marvellous incessant motion. Thin as reeds, apparently they were yet 5 or 6 ft tall.”

The savage Mkodos proceeded to make a woman climb, at spear-point, onto the top of the strange plant and drink the treacly liquid. She became visible intoxicated and then:

“The atrocious cannibal tree that had been so inert and dead came to sudden savage life. The slender delicate palpi, with the fury of starved serpents, quivered a moment over her head, then fastened upon her in sudden coils round and round her neck and arms; then while her awful screams and yet more awful laughter rose wildly to be instantly strangled down again into a gurgling moan, the tendrils one after another, like green serpents, with brutal energy and infernal rapidity, rose, retracted themselves, and wrapped her about in fold after fold, ever tightening with cruel swiftness and the savage tenacity of anacondas fastening upon their prey. And now the great leaves slowly rose and stiffly erected themselves in the air, approached one another and closed about the dead and hampered victim with the silent force of a hydraulic press and the ruthless purpose of a thumb screw.

“While I could see the bases of these great levers pressing more tightly towards each other, from their interstices there trickled down the stalk of the tree great streams of the viscid honeylike fluid mingled horribly with the blood and oozing viscera of the victim. At the sight of this the savage hordes around me, yelling madly, bounded forward, crowded to the tree, clasped it, and with cups, leaves, hands and tongues each obtained enough of the liquor to send him mad and frantic. Then ensued a grotesque and indescribably hideous orgy. May I never see such a sight again.

“The retracted leaves of the great tree kept their upright position during ten days, then when I came one morning they were prone again, the tendrils stretched, the palpi floating, and nothing but a white skull at the foot of the tree to remind me of the sacrifice that had taken place there.”

Heady stuff. Unfortunately, Karl did not exist. Neither did his expedition, the Mkodos, or the tree. They were all the product of a newspaper hoax perpetrated by a reporter named Edmund Spencer. But from that point on, more reports of ‘man-eating trees’ or plants generally began to crop up in newspaper reports and short stories. Here are just a few I have read:

- “The American’s Tale” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1880 (published anonymously)

- “The Man-Eating Tree” by Phil Robinson, 1881 (actually from a travelog)

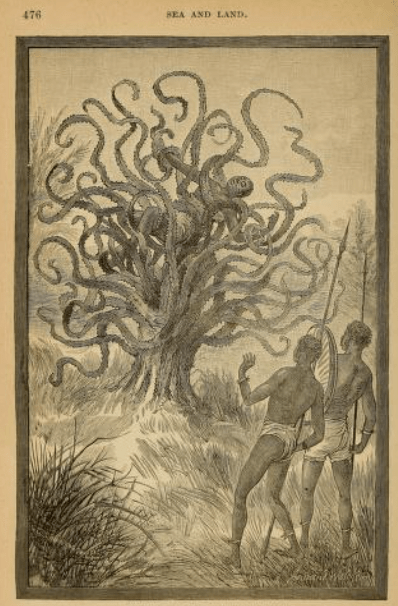

- “The Ya-Te-Vo or Carnivorous Plant” by James William Buel, 1887 (excerpt from Sea and Land, intended as non-fiction, see picture above)

- “Carnivorine” by Lucy H. Hooper, 1889 which brings some mad-scientist elements to the legend and contains the immortal quotation:

“My aim now is to give it locomotion–to see it detach itself from the soil and go forth in search of prey.”

“How can you contemplate the possibility of letting loose such a monster on the world?”

“For science, there is no such thing as a monster. Moreover, are not crocodiles and anacondas and tigers upon earth, to say nothing of the shark and the octopus? Beside these, my creation–my Carnivorine–is a harmless creature.”

- “The Devil’s Snare” by William Thomas Stead, 1891 (also, allegedly, a travelog)

- “The Flowering of the Strange Orchid” by H. G. Wells, 1894

- “The Guardian of Mystery Island” by Edmond Nocini, 1895

- “The Devil Tree of El-Dorado” by Frank Aubrey, 1897

- “Purple Terror” by Fred M. White, 1898

- “The Grotto Flower of El-Banoor” by William Wescott, 1903

- “Professor Jonkin’s Cannibal Plant” by Howard R. Garis, 1905

- “The Orchid Horror” by John Blunt, 1911

By the 20th century, the idea of killer plants with octopus-like or snake-like vines that feed on human flesh or blood, perhaps also with soporific or poisonous flowers or thorns seems to have entered the popular zeitgeist. In the book Orchid: A Cultural History by Jim Endersby (2016) he specifically mentions the connections that were made between the fictitious ‘cannibal plants’ and the increasingly furious scramble for new orchid varieties and thrilling tales of orchid discovery,

“Killer orchids were among the many lethal plants that stalked the suburban greenhouses and the imaginations of their cultivators in the late nineteenth century. By the 1880s, dangerous orchids and other flowers seemed to lurk everywhere, ready to devour unsuspecting humans at every opportunity. This was clearly a popular (and successful) genre, which survived well into the twentieth century, but there seem to be no stories like these before the late 1860s.”

By Mr. Endersby’s estimation, and mine, the closest appears to be “Rappaccini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1844. In this tale, a medical student falls in love with the beautiful but cloistered daughter of a doctor named Rappaccini. Rappaccini has been conducting experiments with poisonous plants and as a result not only the flowers in his garden but also his daughter Beatrice have become untouchably poisonous to humans. Beatrice is not happy with this state of affairs and agrees to drink an antidote and abscond with the medical student…but unfortunately she has become so toxic that the antidote kills her. Unlike her spiritual successor, Pamela Isley, Beatrice is not a seductress, but forever after her man-eating plants would tend towards ‘feminine’ descriptives or associations with victimized, dangerous, or malevolent women. (The film Twice Told Tales from 1963 has a great rendition of “Rappaccini’s Daughter” with Rappacini played by the esteemable Vincent Price).

Referring to some of the killer orchid stories listed above, Endersby continues by writing, “The blood-draining orchids are reminiscent of vampires… and feasting on blood is hardly proper behavior for a plant. In each case, the tropics where the orchids come from are imagined as sinister places, where white manliness seems endangered by uncanny flowers, savage animals, and alien, dark-skinned people…These stories, like much of the literature of the late nineteenth century, are tinged with melancholy, a sense that the sun may indeed be setting on the great European empires because there are no blank spaces left on the map, no new lands to be annexed. Other fin-de-siècle tales have a similar mood, but the orchid stories gave a distinctively biological twist to the wider mood; like Wells’ orchid, White’s [see “The Purple Terror”] has animal-like qualities (the tendrils are compared to the arms of an octopus, and wove with a speed no real plant could match), and the plants seem conscious, able to perceive their surroundings and to stalk their prey. The uncanny quality of these stories is partly created by a blurring of the boundaries between plant and animal…as if the order of nature itself were starting to unravel.”

Endersby then does an excellent job tying the sudden appearance of man-eating plants in the literature of the late 19th century to advances in the plant sciences and botanical evolution, particularly those around real carnivorous plants like the sundew, pitcher plant, and venus flytrap. For more information, I would highly recommend reading Orchid- A Cultural History.

As the 20th century ground on, the short story writing continued, becoming more elaborate and thematic and starting to take the man-eating plant in some unexpected directions:

- “The Pavillion” by E. Nesbit, 1915

- “The Sumach” by Ulric Daubeny, 1919

- “The Green Death” by H.C. McNeile, 1920

- “The Devil Plant” by Lyle Wilson Holden, 1923 (this one is just cribbed directly from the New York World story)

- “The Plant Thing” by R. G. Macready, 1925 (this one is pretty clumsy)

- “Escaped from the Embrace of the Man-Eating Tree” by B.H. William, 1925 (intended as non-fiction, apparently)

- “Dorner Cordaianthus” by Hester Holland, 1925

- “The Woman of the Wood” by Abraham Merritt, 1926

- “The Devil Plant” by John Murray Reynolds, 1928

- “The Ivy War” by David H. Keller, 1930

- “The Plant Revolt” by Edmond Hamilton, 1930 (This one has some top tier villain monologuing)

- A truly bizarre take “Green Thoughts” by John Collier, 1931

- “Seed from the Sepulchre” by Clark Ashton Smith, 1933 (an early example of ‘body horror’)

- “The Moaning Lily” by Emma Vane, 1935 (This one seemed to me the most prescient of Little Shop of Horrors. The lily only moaned, unfortunately, it did not burst into song.)

- “Come Into My Parlour” by Manly Wade Wellman, 1949

- “The Tree’s Wife” by Mary Elizabeth Counselman, 1950

- The first book-length treatment (and subject of a future review) The Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham, 1951

- The adorable “Green Thumb” by Clifford D. Simak where the sentient plant from space is decidedly friendly and not man-eating, 1954

- “Of Withered Apples” by Philip K. Dick, 1954

- The bizarrely trippy “Dr. Adams Garden of Evil” by Fritz Leiber, 1963 which defies easy categorization

In 1935, the ‘cannibal plant’ (of a kind) got its first brief cameo on film with the movie Werewolf of London. In an early scene, the ‘horrible Madagascar plant’ that eats mice and spiders puts in a brief appearance. Surrounded by six massive tentacles, the plant’s furry gullet quickly swallows a frog that is dropped into it by an assistant who calls it ‘my dear Carnelia’. Someone’s immediate response is sheer disgust, “Bringing a beastly thing like that into Christian England!” Which I must say would not be my initial reaction. But perhaps it was somewhat understandable in 1935.

In 1943, Tarzan himself was menaced in the film Tarzan’s Desert Mystery. Tarzan, played by Johnny Weissmuller, travels to a remote prehistoric jungle to gather a rare medicinal fruit. Pursued by Nazi agents, he manages to reach the forest and there encounters giant lizards, giant spiders, and a vampire plant. The vampire plant grabs Tarzan in its tentacles, not unlike the man-eating tree of the Mkodos, but Tarzan yells for help and summons several elephants to tear the vines away and escape.

Other film appearances by man-eating, man-killing or vampire plants include:

- The Land Unknown, 1957

- From Hell it Came, 1957

- Voodoo Island, 1957

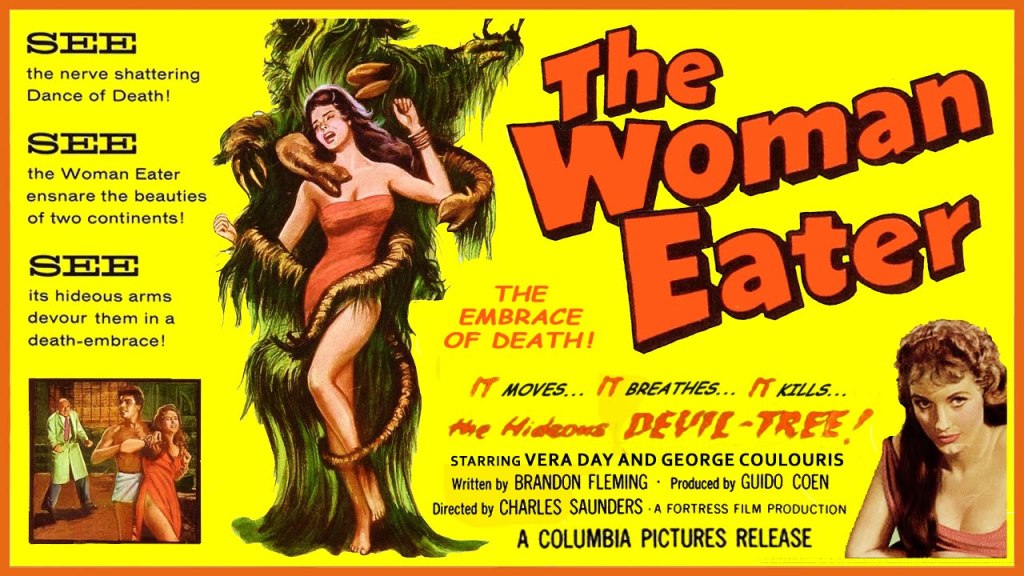

- The Woman Eater, 1958

- The Angry Red Planet, 1959

- The Little Shop of Horrors, 1960

- The Lost World, 1960 (“Well, Summerlee, you may not like vegetables, but they’re certainly crazy about you!”)

- Konga, 1961

- Mothra, 1961

- Invasion of the Triffids, the 1962 movie adaptation

- The first TV appearance of a killer plant with “Specimen: Unknown” an episode of The Outer Limits, 1964

- Die, Monster, Die! 1965

- “The Creeping Vine” segment from Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, 1965 (“Plant like that could take over the world.”)

- The Navy vs. the Night Monsters, 1966 (In which a man is so horrified by the mere sight of ‘the Night Monsters’ that he throws himself through an open door. Of a plane. In flight.)

- Maneater of Hydra, 1967

- When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth, 1970

- At The Earth’s Core, 1976

Man-eating plants hit the big time when Alan Menken and Howard Ashman decided to adapt the 1960 horror comedy The Little Shop of Horrors into an Off-Broadway musical. The original film, produced by B-movie legend Roger Corman, was shot between Christmas and New Years of 1959 for a budget of $35,000, on a bet. According to Corman,

“It only took me two days on a leftover soundstage to shoot principle photography for The Little Shop of Horrors, but it has lived on for nearly thirty years…One reason for it’s astonishing durability is that when I made the film, I was, I believed at the time, virtually creating a new genre– the black-comedy horror film…I was out to create a different kind of film–more cynical, darker, more wickedly funny.’

(How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime by Roger Corman and Jim Jerome, 1998)

The film featured a very young Jack Nicholson cameoing as a masochistic dental patient and a splendid side performance by Dick Miller. According to Roger Corman:

“Dick added his own deadpan style of humor as a customer who sprinkles salt and pepper on Mushnik’s carnations and grazes his way around the shop. It was an ironic twist–a man eating plants in a story of a man-eating plant. “You know,” he says in the opening sequence, “those big places, they’re full of pretty flowers, expensive flowers, and when you raise them for looks that’s when you’re bound to lose some food value.”

Due to the speed at which it was shot and the budget, the movie was limited in scope. The small set, relying mostly on interior shots of the flower shop and a very limited cast of characters translated fantastically when the story was adapted for the stage. And probably continues to contribute to the appeal of the show for high school and community theaters.

The stage performance debuted in 1982 and ran Off-Broadway for several years before being made into a movie in 1986. As in the original film, Seymour Krelborn (Rick Moranis) is a young assistant in a flower shop on Skid Row who grows a very unusual plant. One that he learns needs human blood to survive. He names his plant ‘Audrey II’ after his crush Audrey (Ellen Greene, reprising her role from the stage musical) who also works in the flower shop with him. But Seymour soon discovers that the bigger the plant grows, the more it needs to eat. And Audrey II (voiced by Levi Stubbs) perks up and opens his trap to describe exactly what Seymour should do about the situation. In a loose re-telling of the legend of Faust, the more people Seymour feeds to the plant in exchange for celebrity, riches, love, etc. the bigger and bigger Audrey II grows. This culminates in a showdown between the plant and the man, with the plant aiming for the loftiest of goals–world domination.

In the original stage musical, Audrey II triumphs and eats Audrey, Seymour, and everyone else with the final musical number exhorting the audience “Don’t Feed the Plants”. This ending did not go over well with test audiences, which is a shame, because in the ending originally filmed for the movie-musical Audrey IIs all over the country grow to kaiju size and tear down bridges, crumble skyscrapers, and climb the Statue of Liberty. This rough-cut ending is still viewable on DVDs of the film and YouTube, but the chosen theatrical ending is much happier, with Seymour and Audrey living happily ever after.

The reason I describe Little Shop of Horrors specifically as ‘the big time’ for man-eating plants is because while man-eating plants prior to the villainous Audrey II were certainly threatening and deadly they weren’t really characters. They were often jungle hazards or mad-scientist creations or proxy murder weapons for villainous humans… but Audrey II has a voice, goals, plans. He is a person. This is true in a small part for the 1960 film, but it’s the musical that really contributes to his personality. The movie amplifies this, both through the on-the-money voice acting of Levi Stubbs, and the special effects used to bring Audrey II to life.

In the place of the Audrey Junior from the original movie, primitive and pulled by monofilaments to make the ‘trap’ open and close, and the fairly stationary foam Audrey II’s from the stage performances that are built to be operated by one or two performers, the ‘86 film Audrey II is a wonder of puppetry and hydraulics. Jim Henson’s studio and Lyle Conway, fresh off of Dark Crystal, did the effects work. According to the ‘Making of’ video on my copy of the DVD, building Audrey II required 15,000 handmade leaves, 2,000 feet of vine, 11 ½ miles of cable, and there were 7 sizes of the plant, from a few inches high to the final form at 15 ft.

According to Rick Moranis:

“The plant I think, thanks mostly to Frank and all the people working in that department, the plant has taken on the characteristics of a human. And I feel sometimes when I am working with the plant I’m working with a really ugly guy, you know? Some weird guy with a green head and a big mouth that’s made of rubber…As a character, treating him like a character, almost makes me forget sometimes that it is an inanimate object because he’s so animated at the time I am working with him.”

The film made a modest profit, but saw its biggest sales on VHS. Sadly, the days of having 50 puppeteers and 11 miles of cable on set for practical effects work are gone now, replaced by CGI. CGI has many many advantages and has come a very long way since the early 1990s. But I must say there is something about the weight and palpability of effects like Audrey II that computer-generated effects are seemingly unable to capture. I highly recommend watching the 1986 movie, probably more than once. Look up that alternate ending on YouTube. And, when your local community theater puts on a production of Little Shop, I would suggest seeing it. You will be in for an enjoyable evening.

In researching man-eating plants, it can be difficult to find some of the material. The various short stories can be hard to track down. I found most of them in some convenient anthologies:

- Flora Curiosa: Cryptobotany, Mysterious Fungi, Sentient Trees, and Deadly Plants in Classic Science Fiction and Fantasy, ed. Chad Arment, Coachwhip Publications; Revised ed. edition (December 6, 2013)

- Science Fiction by Gaslight, 2nd edition, ed, Samuel Moskowitz (1974)

- Roots of Evil: Beyond the Secret Life of Plants, Corgi (January 1, 1976)

- Evil Roots: Killer Tales of the Botanical Gothic, ed. Daisy Butcher, British Library Publishing (August 1, 2019) (That has gotta be an authorial pseudonym, right?)

- I first read about the man-eating tree of Madagascar in Searching for Hidden Animals: An Inquiry into Zoological Mysteries by Roy P. Mackal (1980)

The rest of the stories I read were found doing some judicious Googling (see the links below for ones that are available to read online) and scrounging up a variety of out-of-print science fiction and horror collections. Sometimes with disappointing results.

For example, while “Green Thumb” was a tale of friendly alien plants “Green Fingers” by Charles Birkin (1965) turned out to be not a tale of Nazis being fed to man-eating plants which is what I took away from a summary I found, but instead a tale of Nazis using their victims corpses to fertilize a flower bed. Which is a much less appetizing prospect. I also learned from that experience that Charles Birkin apparently had it out for non-white people, lesbians, and a variety of other humans who were not the same as Charles Birkin. So I cannot recommend any collections of his work. There was a general sort of meanness spread throughout.

Another bizarre find was “Odd Attachment” by Ian W. Banks (1991). In this tale a sentient alien tree named Fropome suffers from unrequited love for his sweetheart. Into his melancholic musings a giant ‘seed pod’ falls from the sky and a tiny silver ‘seedlet’ walks out. The tiny silver thing proceeds to shoot some kind of fire at Fropome so he grabs it in his vines and proceeds to pull off its ‘petals’. She loves me, she loves me not… To understand the title, however, you need to read to the story’s end.

Man-eating plants seem to sprout up everywhere. Over in Japan, Godzilla once faced off with Biollante, an enormous hybrid between human, rose, and Godzilla (Godzilla vs. Biollante, 1989). For the youth reader there is More Scary Stories for Sleepovers which has its own tale “Green Thumb” by Q. L. Pearce (1992). Another young reader’s anthology Fright Time has “Night Creatures” by Shannon Donnelly (1995). There’s also the ‘Devil’s Snare’ from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (1997).

As a staple of the jungle adventure, a carnivorous plant makes an appearance in Jumanji (1995). Additionally, the man-eating plant became a weapon of Poison Ivy’s arsenal when battling Batman as seen in the “Pretty Poison” episode of Batman: The Animated Series (1992) as well as Batman and Robin (1997). An AudreyII-esque plant also appears as Ivy’s friend Frank in Harley Quinn (2019). Seemingly every cartoon character from Scooby-Doo to He-Man to G.I. Joe to Kim Possible to Inspector Gadget to Spider-Man seems to have faced off with a man-eating plant at some point or another. Even live-action Tom Cruise was almost grabbed by poisonous ‘doll’s eye vines’ in the 2002 movie Minority Report.

I have not succeeded in hunting down every movie or short story that I have heard about, so my research is ongoing. On my to-read/to-watch list (among many others) are Attack of the Killer Tomatoes (1978) as well as “Subsoil” a 1994 short story by Nicholson Baker that appears to be about killer potatoes. I look forward to reading it. I have had no luck tracking down The Unholy Goddess and Other Stories by Wyatt Blassingame (2011) which supposedly contains a killer plant. I do have a copy of The Seeding by David Shobin (1984) on my shelf, the cover art of which has a sinister purple orchid, but I suspect that there are not in fact any killer plants in there. We’ll see. I also must re-read the confusing short story “Growing Things” in Paul Tremblay’s 2019 short story collection with the same name. I could not quite decide last time if that plant counted.

Man-eating plants will not be going away any time soon, though compared to their horror staple brethren like vampires, werewolves, or ghosts, I suspect they will always be harder to find. As the years have gone on their associations with travelogs, tropical jungles, and belligerent natives have continued, but they have also been taken in unexpected directions. They have become the product of mad science, invaders from outer space, and had a persistent link to the devilish and demonic. While real life carnivorous plants are small, inoffensive creatures, the ‘devil plants’ of the imagination are pitiless, creeping terrors, eager to draw their warm-blooded prey to a sinister and leafy doom.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to run. My wife is making gardenias.

Stories and excerpts you can read free and in full online:

“The Man-Eating Tree of Madagascar”, reprint of the New York World story in the South Australian Register, Oct. 27, 1874:

“The American’s Tale”, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1880:

https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php/The_American%27s_Tale

“The Man-Eating Tree” from travelog Under the Sun by Phil Robinson, 1881:

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Under_the_Sun/The_Man-Eating_Tree

“The Ya-Te-Vo or Carnivorous Plant” from Sea and Land by James William Buel, 1887:

https://archive.org/details/sealandillustrat00buel/page/476/mode/2up

“The Devil’s Snare”, William Thomas Stead, 1891:

https://hatch.kookscience.com/wiki/La_Sagenas_de_Diable,_the_Devil%27s_Snare

“The Flowering of the Strange Orchid” by H. G. Wells, 1894:

https://www.online-literature.com/wellshg/2865/

“The Devil Tree of El-Dorado” by Frank Aubrey, 1897:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43944/43944-h/43944-h.htm

“Purple Terror” by Fred M. White, 1898:

https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks11/1100781.txt

“Professor Jonkin’s Cannibal Plant” by Howard R. Garis, 1905:

https://www.fadedpage.com/showbook.php?pid=20210655

“The Pavillion” by E. Nesbit, 1915:

https://en.m.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Pavilion

“The Devil Plant” by Lyle Wilson Holden, 1924:

https://archive.org/details/WeirdTalesV01n03192305/page/n91/mode/2up?view=theater

“The Plant Thing” by R. G. Macready, 1925:

https://archive.org/details/WeirdTalesV06N01192507/page/n67/mode/1up

“The Woman of the Wood” by Abraham Merritt, 1926:

https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0602041h.html

“The Devil Plant” by John Murray Reynolds, 1928:

https://archive.org/details/Weird_Tales_v12n03_1928-09/page/n143/mode/2up

“The Plant Revolt” by Edmond Hamilton, 1930:

https://archive.org/details/WeirdTalesV15N04193004jvhSas/page/n73/mode/2uph

“Seed from the Sepulchre” by Clark Ashton Smith, 1933:

http://www.eldritchdark.com/writings/short-stories/191/the-seed-from-the-sepulchre

“Of Withered Apples” by Philip K. Dick, 1954:

https://americanliterature.com/author/philip-k-dick/short-story/of-withered-apples/

Leave a reply to The Plants by Kenneth McKenney – Lady Scientist Reads Cancel reply