In a half-remembered time a few years ago now, I had a great many rambling thoughts and feelings about feathered dinosaurs as movie monsters and wrote them down. After reading Relic I am not ready to embark on a full Jurassic Park review quite yet, but I figured I would post this here as it does a good job laying out thoughts I have had on what exactly makes monsters scary and many of the points are directly applicable to Relic, Natural Selection, and other books I intend to review here.

Thesis Statement:

Feathered dinosaurs are still intimidating and deserve their day in the sun.

The Facts

Since Archaeopteryx was discovered in 1860, possessing a long, bony tail, vertebrae with air sacs, and feathers, it has been known that dinosaurs and birds have a close relationship. Of all the dinosaurs, the dromaeosaurs seem to have the most in common with birds. Dromaeosauridae is the family of dinosaurs that includes such august members as Velociraptor and Deinonychus. They are now colloquially known as ‘raptors’ due to a certain popular film. These bird-like dinosaurs have half-moon shaped wrist bones, three-fingered hands (modern birds have these finger bones fused together), an upright stance, four-toed hind feet with the first toe reversed, highly vascular bones, and were probably homeothermic with muscular, divided hearts, just like modern birds. Birds are now considered to be a type of dromaeosaur!1 But were dromaeosaurs fluffy? Some thought they might be, but evidence was slim. Well-researched paleoart of dromaeosaurs from the mid-twentieth century makes them look suspiciously ‘plucked’.

After decades of speculation, fossil discoveries in Liaoning, China in the 1990s confirmed that some dinosaurs possessed not a tuft here or there, but fully feathered bodies with well-feathered, proto-wing-like forelimbs. The more fossils that have been found, the stronger the conclusion: feathers were a widespread feature in predatory dinosaurs.

If they couldn’t fly, why did dinosaurs have feathers? What were they used for? Theories vary on this front. They could have been used for insulation, especially when brooding eggs. They could have been used for mating displays, signaling sexual fitness. Or maybe they could have been used for balance. More on that later.

Back to the dromaeosaurs. In the late sixties, a paleontologist named John Ostrom described Deinonychus, a dinosaur whose name means ‘terrible claw’, from fossils found in the early Cretaceous rocks of Montana. He hypothesized, based on the dinosaur’s morphology, that it was a highly active animal with a large brain, a challenge to the paleontological orthodoxy of the time that painted dinosaurs as slow, stupid brutes. Deinonychus, he said, was capable of rapid movement and sustained levels of activity. With a large brain and large forward-facing eyes, sharp, backwards curved teeth, long grasping hands with cutting-blade claws, powerfully built and modified hind legs, and a stiffened tail to work as a counterbalance and rudder, Deinonychus was a superb predator. The pièce de résistances were the five-inch sickle-shaped claws that gave the animal its name. Located on the second toe of each foot and held carefully off the ground to maintain sharpness, these terrible claws could be used as offensive weapons, driven into the soft flesh of prey with kicks of the powerful legs2.

At ten-feet-long and about six-feet-high, with a weight around 150 lbs, Deinonychus was larger than the six-foot-long, three-foot-high Velociraptor. There was, for some time, a confusion between fossils of one and fossils of the other, so some Velociraptor size-estimates ended up inflated, which had consequences for a certain popular film. *cough*. The family did contain larger members. Described in 1993, Utahraptor clocked in at fifteen to twenty-feet-long, around 600 lbs. (about grizzly bear weight), with nine-inch sickle claws on its feet.

It’s easy to see how members of the family ended up recruited for Hollywood magic. Richard Fortey in his book Life calls them “the scariest hunters of all”: “Velociraptor were shown hunting in packs, running down their prey. Grisly enthusiasm for the chase and a startling intelligence made them the animals that linger longest in nightmares when the film is over. They were even seen problem-solving—opening a door at one point in the story.” As someone who has, indeed, had nightmares involving Jurassic Park-style Velociraptors, I can confirm this. But how much truth was there in the scare?

Well, Ostrom did think that dromaeosaurs might have hunted in packs. Some Deinonychus fossils were found together, grouped around a larger herbivore. He hypothesized that they had been pack-hunting when they met their untimely demise. But, recently, a study of the fossils and the behaviors of living dinosaur relatives like Komodo dragons, alligators, and predatory birds, has called the pack-hunting theory into doubt (“A Reevaluation of Cooperative Pack Hunting and Gregariousness in Deinonychus antirrhopus and Other Non-avian Theropod Dinosaurs” Roach, Brinkman, 2007). Perhaps the raptors hunted alone.

How about the snapping jaws? Capable of severing Samuel L. Jackson’s arm? It is estimated that Deinonychus had a bite force greater than living carnivorous mammals, including the hyena, able to bite through bone, equivalent to an alligator of similar size (“A description of Deinonychus antirrhopus bite marks and estimates of bite force using tooth indentation simulations” Gignac, Makovicky, Erickson, Walsh, 2010).

Would Deinonychus have been able to call to one another? Modern birds are certainly able to communicate with each other. But modern birds possess a vocal organ called a syrinx (while other close dinosaur relatives, the crocodilians, produce sounds using their larynxes). The syrinx, “a series of cartilage rings at the junction of the trachea and primary bronchi…can be vibrated to produce sound”. But no osteological indicators of such an organ have been found in non-avian coelurosaurian theropods, or in any dinosaurs. “The lack of evidence of a syrinx in ornithodirans outside Ornithothoraces will, no doubt, disappoint fans of roaring movie dinosaurs. However, lack of ability to vocalise does not necessarily mean that such animals were silent altogether. Many extant reptiles communicate with each other and with potential predators by non-vocal acoustic means such as hissing, clapping jaws together, grinding mandibles against upper jaws, rubbing scales together, or use of environmental materials (e.g. splashing against water)…Birds also use non-vocal acoustic means of communication such as hissing, bill-clapping, stamping and wing beating…Non-avian theropods with feathered wings may have beaten their wings in acoustic displays as extant birds often do” (“Voices of the past: a review of Paleozoic and Mesozoic animal sounds” Senter, 2009). Several kinds of living birds, including cassowaries and Great Bitterns make vibration-based rumbles and booming sounds. These and the vibration-based sounds of alligators and crocodiles are probably as close as living animals come to approximating the sounds of non-avian dinosaurs.

Would the ‘raptors’ be fast enough to catch a human? A rough walking speed estimate based on trackways (fossil footprints) indicates a walking speed of 6 miles per hour (“The walking speed of dinosaurs from the Peace River Canyon, British Columbia, Canada” Kool, 1981). Not much when compared to modern flightless birds like the ostrich. But ‘slower than an ostrich’ is still plenty fast. Particularly when you are an ambush predator. The average woman jogs at a speed of 6.5 miles per hour. I leave you to your own conclusion.

What about their intelligence? Figuring out the intelligence of an extinct creature is impossible, but we can make a few guesses. Based on the shape and size of the brain cases of other dromaeosaurs, large optic lobes, large olfactory bulbs, etc. Deinonychus likely had a sophisticated sensory system and brain, a well-developed sense of balance, and complex nervous and muscular coordination. “The large olfactory bulbs of…dromaeosaurids may indicate that they were active in low-light conditions or may reflect the importance of olfaction for certain activities (e.g. location of food sources, navigation in large home ranges)” (“Olfactory acuity in theropods: paleobiological and evolutionary implications” Zelenitsky, Therrien, Kobayashi, 2008). The field of vision of dromaeosaurs was likely “similar to those of modern raptorial birds”; Velociraptor specifically had a field of vision “comparable to that of owls” (“Binocular Vision in Theropod Dinosaurs” Stevens, 2006). This means dromaeosaurs, with their stereoscopic vision, could see in 3-D and judge distances. With all this sensory input to process, a bigger brain relative to their body size makes sense. But with guesses for smarts that hover in the realm of ‘maybe as intelligent as a modern bird’ (which bird?!?) there’s plenty of room for speculation.

Even if they were intelligent enough to figure out doorknobs, it is unlikely that Deinonychus would ever have been able to open one, for the simple reason that “Supination and pronation cannot occur by movement of the radius, which is immobile relative to the ulna”. Which means that the fancy twisting that our wrists do when we open a door was completely beyond the abilities of a dromaeosaur. However, “The morphology and range of motion in the forelimbs of Deinonychus and Bambiraptor enable two-handed prehension [grasping] with the wrist flexed, one-handed clutching of objects to the chest, use of the hand as a hook, arm-swinging or raising displays, and use of the forelimbs to maintain balance” (“Comparison of Forelimb Function Between Deinonychus and Bambiraptor” Senter, 2006).

Which brings us to the feathers. In 2011, Fowler, Freedman, Scannella, and Kambic published “The Predatory Ecology of Deinonychus and the Origin of Flapping in Birds”. In this study they drew attention to the similarities between the sickle claw of Deinonychus and the talons of modern predatory birds. What if, they postulated, instead of pack hunting much larger herbivores as was commonly accepted, the ‘raptors’ instead behaved more like their modern namesakes? In modern raptors, the extant accipitrid birds of prey, “the talon is used to maintain grip on prey of subequal body size to the predator, while the victim is pinned down by the body weight of the raptor and dismembered by the beak”. And how much more easily could prey be dismembered by recurved teeth? But this study made one more important point, while standing atop their prey, modern raptors flap to stay balanced. This “stability flapping” might hold the key to both an adaptive advantage conferred to the feathery dromaeosaurs and to the evolution of flapping strokes that, ultimately, led to flight in avian dinosaurs.

The Objection

But feathery dinosaurs aren’t scary enough, people on the internet whine:

“Changes like that kill the imagination engine. When you look at the dinosaur art being done today, it’s remarkably depressing, especially if they’re correct that all the raptors were feathered. Depicting them like that makes them no longer dinosaurs anymore. The great and powerful Oz will have been reduced to a funny little man. Dinosaurs would then just be birds instead of mysterious monsters, and our collective imagination would be reduced to that annoying kid in the first “Jurassic Park”: “That doesn’t look very scary. More like a six-foot turkey.” Who wants to go to a movie about a six-foot turkey?” – Aaron Gleason, “The Real Reason Feathered Dinosaurs Won’t Appear in Jurassic Park Has Nothing to Do with Science”, The Federalist, 2018

Yes. An actual man wrote an actual article about this. To demonstrate the complete inanity, let’s do a little thought exercise. Take for example, the Northern Goshawk, Accipiter gentilis. Look at that! One of those accipitrid birds of prey from before, related to the kites, eagles and hawks. How did “The Predatory Ecology” describe their feeding? “Death of the victim is hastened by massive bleeding from wounds sustained whilst being eaten alive”. The Northern Goshawk is the largest bird in its genus at around three pounds. They are identifiable by their large red or orange eyes and brownish gray to gray coloring with darker barring and streaks. All the better to blend into the treetops. According to the Audubon Society website, the Northern Goshawks “take their prey by putting on short bursts of amazingly fast flight, often twisting among branches and crashing through thickets in the intensity of pursuit”.

The Northern Goshawks are solitary, ambush predators. Except, of course, when you are near their nest. They mate for life. And the female generally grows larger than the male. They are highly territorial. They hunt silently. Mostly. They don’t want their prey to hear them coming. But according to animalia.bio “occasionally hunting goshawks may make shrill screams when pursuing prey, especially during a lengthy chase and the prey is already aware of its intended predator”. In addition, “Northern goshawks often leave larger portions of their prey uneaten and sometimes cache prey on tree branches or wedged in a crotch between branches” (animalia.bio). They are diurnal, like we are, so they hunt during the day “They glide quickly and silently, striking unwary quarry feet first. If detected these reckless hunters fly at high speeds in pursuit of fleeing prey, maneuvering through the forest using their long tail as a rudder, crashing through brush and even chasing a potential meal into water if necessary (Cornell Lab). They will go into the water on foot to grab their prey.

And then the prey is pinned down by the talons, organs punctured, spine snapped, and dismembered. Still alive.

But still? A three-pound bird? Who’s scared of that?

…Try to imagine yourself in the early Cretaceous period. You are walking through the forest, convinced you are alone. There are no sounds beyond the buzz of insects, the screeching of pterosaurs, a few small avian dinosaurs in the trees, the rustle of leaves. The sun beats down through the branches above you. It’s very warm…but you get a bit of a prickle on the back of your neck. The birds have stopped singing.

You turn around and in the thicket behind you, you spot two bright red eyes, each the size of a half-dollar.

They’re watching you.

Almost as soon as you process this, the bushes explode! And a body, nearly equal to yours in size, crashes through the brush. It makes no vocalization besides the heavy panting of its breath. With grey and brown feathers, striped and speckled with black, the predator blended in perfectly with the shadows and dead wood of the forest. It could have been stalking you for minutes and you would never have known.

You run, as fast as you can, ducking around trees and zigzagging like mad. It can’t catch you right away, too much plant matter in the way. The thickness of the forest covers your escape. You duck to the right and it follows behind you, stiff tail acting as a balance and a rudder, allowing it to turn on a dime.

If only you could make it to the river.

Just as you spot the water shimmering beyond the trees. A thick, bone rattling rumble rises from the thing’s throat, nearly paralyzing you with terror. You duck under a log and lunge for the water.

You make it a few steps into the current when a weight crashes into your back. You fall forward, palms first into the muddy river bottom. Feathers flash around you, throwing up spray, and something like a steak knife drives itself into your spine. A scream is strangled in your throat as water rushes into your mouth.

You can’t feel your legs.

Dozens of sharp points close on the back of your neck, piercing the skin. You can feel the predator’s hot, stinking breath. Dragged from the water, you struggle feebly on the sand, but the weight bears down on you again and you can barely move. You don’t have enough air in your lungs to scream.

Blinding pain and you turn to look. All that’s left of your left hand is a bleeding stump. The predator above you presses down, inexorably. It’s wings brush against your exposed back as it tears at your detached extremity, grasping it between two razor-clawed hands, the primary feathers anchored to its second fingers soon matted in blood.

The sand around you is turning red.

Rip. Something…something from around your kidneys this time. A large piece. You feel a bit less of the pain, like a fog is descending even though it’s early afternoon. Everything is going black.

You wake a few seconds later. Or maybe minutes. Either way, it’s much darker. There are spots hovering in the air. You’re draped over a dead log.

Your right hand and most of your arm is missing now. Blood pumping out of your body in a wet splatter. A soft huffing sound from above. Looking up through glazed eyes you see them, the predator has joined another. A larger one. His mate.

She looks down at you through big, red eyes and reaches down, feathery head bobbing on her curved, bird-like neck to rip out your throat.

So, you know, Aaron. Try to show a little respect.

Going Forward

Dromaeosaurs were not the only feathered dinosaurs. Since feathers are unlikely to have evolved more than once3, it can be extrapolated that whenever feathers appeared in the dinosaur fossil record, all descendants of those dinosaurs were probably feathered to some degree. Slowly, the branches of the dinosaur cladogram that have feathered dinosaurs perched on them have expanded. From birds, Archaeopteryx, dromaeosaurs, and troodontids in the clade Paraves out to oviraptorosaurs and therizinosaurs (which were herbivores!) in the larger clade Maniraptora, out to ornithomimosaurs, compsognathids, and tyrannosaurids! All coelurosaurs, the clade encompassing all these groups, are now thought to have been feathered! And, yes, that means the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex too. Not all theropod or ‘meat-eating’ dinosaurs fall into this clade. Carnotaurus, for example, or Dilophosaurus, Allosaurus or Spinosaurus, are all outside the range of Coelurosauria. Carnotaurus skin impressions have been found for many different parts of the body and they have all shown a uniform coat of pebbly scales, with no feathers in sight. Maybe only coelurosaurs had feathers?

There are some occasional challenges to this conclusion. In 2012, the discovery of Sciurumimus a possible megalosauroid from the late Jurassic with filamentous plumage, was heralded as the discovery of the most basal yet feathered theropod. Branching off from the theropod family tree before the coelurosaur split, it looked as though all theropods might have had feathers (“Exceptionally preserved juvenile megalosauroid theropod dinosaur with filamentous integument from the Late Jurassic of Germany” Rauhut, Foth, Tischlinger, Norell, 2012). But the phylogenetic placement of Sciurumimus is still being debated. And the debate will continue as new evidence comes to light.

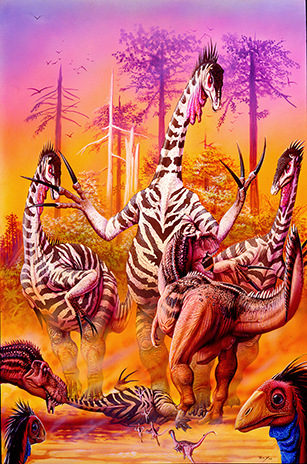

In concert with all the new data gathered on feathers in dinosaurs since the 1990s, many paleo artists have stepped up to the plate to depict these creatures in all their feathery glory. Very early on, beginning in the 1980s, Luis Rey made a point of depicting feathered dinosaurs (though some are a bit naked by today’s standards) in a variety of eye-popping colors. His book A Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2003) is where I first saw feathered therizinosaurs and dromaeosaurs and oviraptorosaurs, leaping out from the pages as I skimmed through it at the public library.

My current favorite is Jed Taylor. He was only seven when Jurassic Park came out and has maintained a life-long interest in dinosaurs. Prompted by the Jurassic World ‘no feathers’ debate he began drawing ‘raptors’ in earnest around 2013. And they are magnificent. If you combined ducks with wolves. No, meaner than ducks… If you combined geese and wolves, you would end up with something close to as intimidating as his raptor reconstructions. They look alert, thoroughly bird-like, and fully capable of ripping you apart. Their feathery, taloned feet in particular remind me a lot of the lethal fluffiness of snowy owl feet.

In the future, I would love to see a raptor reconstruction like these on film. With computer-generated images having come so far since 1993, it is technically feasible. And given the right lighting, some sound effects, a musical score…I think they could be just as terrifying as their improbably flexibly wristed, naked, toe-slashing brethren.

Note: The Making of the Ultimate Predator

But what makes an effective movie monster? Why were the raptors of Jurassic Park so memorable and fear-inducing? How does an animal graduate from natural predator to nightmarish bogeyman?

Let’s examine the scene that freaked me out most from the first Jurassic Park movie: a raptor pursuing Ellie Sattler through the generator tunnels. There are a couple things in this scene that combine to make it even creepier than the ‘raptors in the kitchen’ scene. The tunnels are darkly lit, they are unfamiliar and claustrophobic, Ellie could easily get lost and she needs a flashlight to see. She is alone, with the only help she could call is too far away to matter. Then, once the lights are back on, a raptor leaps out of nowhere! Ellie’s avenues of escape are cut off and she is trapped! She is being hunted by unseen predators and cannot predict where they will strike next! I don’t think I have to explain why a severed arm falling onto you is terrifying. Severe injury, blood and gore, and death are self-evidently unpleasant to most of us. It doesn’t help that Ellie is injured and cannot run away as fast as she normally would, even once she gets out in the open. This all combines into a pretty tense three or four minutes. I would argue that as terrifyingly toothy and clawed and scaly as the raptors are, a lot of the tension here stems from the environment more so than the type of predator hunting Ellie.

A dark, labyrinthine, isolated location where visibility is limited and every creak might be danger? I would compare the setting to the ubiquitous haunted house. In his article, “A psychologist explains why haunted houses terrify us” Frank T. McAndrew explains: “From a psychological point of view, the standard features of haunted houses trigger feelings of dread because they push buttons in our brains that evolved long before houses even existed. These alarm buttons warn us of potential danger and motivate us to proceed with caution”. These alarm buttons are called “agent detection mechanisms— or processes that have evolved to protect us from harm at the hands of predators and enemies”. Things that can trigger agent detection mechanisms include sudden sounds, movements, or smells, changes in temperature, anything that could indicate the presence of an unseen predator. McAndrew writes, “We are constantly–even unconsciously–scanning our surroundings and assessing our ability to flee if it should become necessary”. Like the generator tunnels, and the under-staffed, storm plagued, phoneless Jurassic Park itself: “The prototypical haunted house is in a remote, isolated location, far removed from the rest of society (think of the off-season resort hotel in The Shining, for example). If bad things do happen, help would be a long time coming, even if communication with the outside world were possible. (Conveniently, in old horror movies the telephones always stop working.)” Features of such places include: darkness and reduced visibility, confusing layouts, and features that impede sight and escape. There is a delicate balance humans try to maintain, McAndrew writes, between “prospect” and ‘“refuge”, or the balance between having a safe place to hide from danger vs. having a clear, unobstructed view of the landscape. Haunted houses are all about the obstructed view. A lack of legibility or “the ease with which a place can be recognized, ordered into a pattern and recalled…a place we can wander around in without getting lost” is also a feature of haunted houses. As unfamiliar ground, Jurassic Park has that in spades (“A psychologist explains why haunted houses terrify us” by Frank T. McAndrew, October 23, 2019 on fastcompany.com).

So could Spielberg have had just any animals menacing his cast in the isolated setting of Jurassic Park? I would say no. There have been many, many horror movies made over the years (Jurassic Park is not one, despite having some of the elements of the genre) starring all kinds of monstrous creatures from blobs of jelly to alien vegetables to gila monsters to praying mantises. But not all animals have equal scare potential. I believe I have already made my point about feathers as a disqualification, but I do think that animals that are predators have the edge here.

Perfect example, in 1972 a film called Night of the Lepus was released. Genetically engineered creatures escape from a lab and begin to breed in dark and creepy abandoned mine shafts. They come out at night to hunt human prey, tearing apart vehicles and buildings. The bloody remains of their victims are found strewn over wide areas, terrifying the residents of the small and isolated towns in the area. Finally an entire pack of the creatures emerges and has to be stopped. Sound like an effective horror movie? It could have been…except ‘lepus’ is Latin for rabbit. The monsters were giant, mutant bunny rabbits. And no amount of dubbing in of heavy panting or gallons of bright pink 70s blood could make bunnies seem terrifying. I still have no idea what MGM was thinking. Your monster of choice should have something going for it: speed, acid, fangs, claws, venom, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes–something that gives it a predatory edge over humans. And it helps if it is not lop-eared-bunny-cute. Probably. Unless you are in a Monty Python sketch.

But there’s one thing your monster should do for sure, and that’s leap out of unexpected places. Matt Kaplan lays it all out in his book Medusa’s Gaze and Vampire’s Bite, his go-to example is the eponymous Alien of Alien (1979): “At its most basic level the terror of this story is hardly new. The alien almost always attacks from dark alcoves, ventilation ducts, and tunnels. It emerges silent and unseen until it is too late for its victims to escape. This is identical to the behavior of many modern predators. Numerous great cats sneak up on mammals that they are keen to eat. The same goes for a number of sharks, including great whites, that sit in the dark depths below their surface-swimming prey and lunge forward to attack only when they think they have the element of surprise. The monster in Alien is playing off of the ancient fear of predators that sits deep within the mind of every human being”. The ship Nostromo here fills in as the isolated and maze-like haunted house. But in space. “Stalked relentlessly by a carnivorous beast, one by one the crew are ripped apart and consumed. It is impossible to find on the shadowy ship, and it makes its attacks almost entirely unseen…There is no escape and no rescue on the way, because “in space no one can hear you scream.”” Matt Kaplan observes that, “For most people today, there is not much reason to worry about being hunted” (Medusa’s Gaze and Vampire’s Bite: The Science of Monsters by Matt Kaplan, 2012). Logically, we know this. But illogically…I think we’ve all walked around a house at night, maybe our own house, maybe just to get a glass of water. And we’ve all heard a creak or a knock or a scraping sound and gotten that fearful shiver, envisioning all kinds of monsters or enemies preparing to attack…but then we remember the water heater knocks and go back to bed. But for that brief moment, we feel what it is to be hunted.

Drawing on Kaplan’s comparison to shark ambushes, the oceans demonstrate another excellent environment to populate with monsters. Humans can swim, but we are not fast. We can see underwater, barely, and nothing much below us when we’re swimming. The legibility of the environment is meaningless when we can’t hold our breath for more than a few minutes at best. The balance between prospect and refuge is upset. There’s nowhere to hide, you can’t see, and running away is out of the question. Many of us swim alone, or at least separate somewhat from a group in the water. It is an alien environment. No wonder then that shark attack is such an enduring fear, both on film and off.

Richard Fernicola opens his book about the 1916 New Jersey shark attacks with the observation that apex predators implicated in human deaths like polar bears, Nile crocodiles, or tigers aka “visible terrestrial predators”, while terrifying, inhabit the dry land we call our home. In contrast, Fernicola writes, “What is so terribly disconcerting about this scenario [shark attack] is that the ocean is an environment that hinders both our ability to see the approaching danger and complicates our most natural and effective means of escape. The shark, on the other hand, is the master predator of its domain. Conditions that are only marginal for human comfort and survival are the same conditions that allow this powerful creature to spring suddenly and mercilessly upon us”(Twelve Days of Terror: A definitive investigation of the 1916 New Jersey Shark Attacks by Richard Fernicola, 2001). The best film example of this, of course, being Jaws (1975).

Jaws checks off all the boxes that Alien and the Jurassic Park raptors do, especially the film’s final act. Radios are out, calls for help unanswered or answered too late. A silent and unseen predator attacking from nowhere, almost impossible to track. The fear of being ripped apart and eaten. The limited visibility and non-existent hiding places for humans. And, of course, a twenty-five foot Great White fits the predator bill well. Many Jaws imitators popped up in the years following its release. While Night of the Lepus was made in the style of 1950s monster movies, Jaws kicked off a new style and genre of ‘animals attack’ film, gorier and less reliant on mutating radiation. Grizzly (1976), Piranha (1978), Barracuda (1978), Orca: The Killer Whale (1977), Crocodile (1979) Alligator (1980), Tentacles (1977), and the Italian-made Great White (1981) are all prime examples.

In the immediate wake of Jaws, there were movies made about killer bees, worms, rats, slugs, dogs, frogs, ants, wild boars, crabs, clams, bats, cats, sea serpents, and the Loch Ness monster. And, predictably, the fearsomeness (and competency of the technical effects used) of the animal in question had a lot of bearing on whether the movie was a little laughable or mostly laughable. Rarely have I found them even a fraction as scary as Jaws or Alien. Or, for that matter, certain scenes from Jurassic Park. I did enjoy Prophecy (1979). I think it’s one of the better ecological horror films made. And it accomplishes the stalking of its cast through an isolated setting by a deranged predator well. But Jaws it is not.

Keeping these factors in mind, nothing about feathered dinosaurs would prevent them from being truly fearsome movie monsters. And many other candidates could be suggested as well. Starting with the criteria of:

- remote, isolated location with obstructed views and lack of legibility

- a small number of humans and reduced communication with the outside world

- a predatory creature that leaps out of unexpected places and rips its prey apart

A variety of movies could and have been made. Apart from the 1950s B-movies with giant bugs, extraterrestrial beasts, etc. and the 1970s/1980s ‘animals attack’ movies made in the wake of Jaws, other notables include: Tremors (1990), Anaconda (1997), The Relic (1997), Deep Rising (1998), Lake Placid (1999), and Deep Blue Sea (1999). And those are just a few from a single decade. But they all leverage the formula of isolated setting, reduced communication, and nightmarish ambush predator(s). If that predator happens to have been based on a real creature, it is usually enhanced in some way to be extra fearsome or intelligent or large (the beast from Anaconda looks and behaves almost nothing like actual anacondas).

As a final, slightly off-topic, note, I would like to mention two films that take this formula to the next level. First, Predator (1987) in which the formula is followed rigorously, but with the added threat of the creature not only being a non-human alien predator but also a hunter who embodies some very human tendencies. Say what you will about sharks, snakes, crocodiles, and even Alien, but they don’t skin their prey and hang their skulls like trophies. Humans do that. And in many other movies, the role of lurking monster is straight-up assigned to an actual human, no fangs or claws needed. For example Halloween (1979) and it’s ilk. The second film I would like to mention is The Thing (1982).

The Thing occurs in one of the most inhospitable and isolated settings on Earth, Antarctica, at a research station during the six months of darkness. It’s remote, dark, visibility and livability are poor, and the shadowy hallways of the research station (as well as the frozen husk of the Norwegian station) provide plenty of ‘obstructed view’. Communication is cut off, the action is limited to a small and shrinking group of humans who must band together to survive. The Thing itself is a monstrous melding of tentacles, crab-like legs, fangs, claws, oozing goo, writhing viscera, and human limbs. And it can attack from an unexpected angle.

But the real stroke of brilliance is that, while Alien and Jaws can camouflage using their environments and The Predator can make himself invisible using technology, The Thing can hide in plain sight. “Man is the warmest place to hide” as the tagline says. In The Thing, the other people, your friends and coworkers, the very people you are depending on for survival? They could all be The Thing. But, at least you know that you are human…or are you? The fears of death and injury, haunted houses, ambush predators, even headhunting all pale in comparison to the paranoia of not being able to trust the people close to you and then losing your identity, losing your soul, and becoming someone, something else. Something not human. That’s what makes The Thing one of the scariest movies I have ever seen.

Update (2022):

So, above, I discussed a bit about the history of feathered dinosaurs and why feathered dinosaurs could still be intimidating predators. I also discussed the balance between prospect and refuge, ambush predation, and how the environment can contribute to making effective movie monsters. I even discussed water predation specifically. Then I stopped writing and went about my life for several years. And then they made Jurassic World: Dominion.

And it was…weird. Not for the reasons I thought it originally would be, i.e. a population of maybe fifty dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures somehow thriving and considered a threat (I mean, think of endangered species today that have thousands of individuals of the same species, living in their natural habitats with some of the best protection humans can muster and that are STILL going extinct. And they evolved to live in modern, extant habitats. But, somehow, a 40-foot Tyrannosaurus can elude Animal Control for an entire year?!? To paraphrase the illustrious Alan Grant “They’re not monsters…they’re just animals.” Animals as big as bulldozers that can rampage through the continental U.S. and somehow not be detected for months, apparently…) But that was the kind of nonsense I was expecting based on the last entry in the film series. Which, for the record, I enjoyed. I liked Chris Pratt’s turn as a John McClane-esque man of action, I liked the hideous creeping gait and Joker-like smile on the Indoraptor, I liked the cloning subplot, it was good fun. But Dominion went in some unexpected directions.

There were parts I objected to on story-related grounds: too many cast members, not enough development to go around, limited use of the returning members of the talented original cast, and a general fear of risk taking. The whole script seemed to be playing it safe. If they had had any cajones, Ian Malcolm would have gotten dramatically eaten or at least injured in that scene where he’s just standing outside the Dimetrodon-infested tunnel. And instead of generic corporate villain #4, who I think was attempting a poor man’s Steve Jobs, one of our three OG cast would have been the surprise villain. And they would have had a cooler plan than whatever locust-related shenanigans were afoot. I think it would be a toss-up between Malcom and Grant, actually. They both have previously played the anti-Christ during their film careers. Also a missed opportunity to resurrect Sam Jackson’s character. Or have his estranged twin brother or something pop up. I think Sam Jackson would have said yes. They could have had him Captain Ahab it up like he did in Kong: Skull Island (2017) (another movie with too many cast members with not enough to do, incidentally.)

But story issues aside, what was the deal with the feathers?!? They bring in my favorite dinosaur of all time, Therizinosaurus, and make him gray colored and barely fluffy? A complete badass, which is fair, and nice that they remembered that even herbivorous wild animals can be dangerous (hippos, rhinos, moose, etc.) But his design is a far cry from Luis Ray’s hot pink and zebra-stripes model (my favorite) pictured below. And then, oh boy, we have Pyroraptor.

I had never heard of the genus before but just a cursory Google showed me that the Jurassic World: Dominion version looked nothing at all like the real thing. For one thing, it was too big. My superficial Googling showed me a Pyroraptor weighing about 20 lbs. and coming up to an adult human knee. Terrifying. (Well, maybe if there was a whole swarm of them…)

But it had feathers! And was shown living in snow. Parts of the earth were cold during the dinosaur ages; there were plenty of Antarctic dinosaurs who probably experienced snow, for example. So that was a nice change of pace. Also the feathers had some color, rusty red, which we know some dinosaurs actually had! 4

So I was excited about that…and then the Pyroraptor proceeded to attack Chris Pratt and Kayla (our Han Solo for the duration) by diving into the water and swimming underneath them.

*pinches bridge of nose*

Look, I appreciate the effort. But when I mentioned shark attack as particularly nail-biting I didn’t mean that I thought all movie monsters should do it! Especially non-avian dinosaurs, none of whom have even been found with evidence of an aquatic lifestyle. Other than Spinosaurus, of course. And, yes, many extant birds can hunt in and around water. But the Pyroraptor and its plumage looked nothing like penguins, cormorants, herons, ospreys… It looked very shaggy and un-hydrodynamic.

Although now that I think about it Alien: Resurrection, The Relic, even Prophecy all had scenes of attacks from underwater… even though they did not have ‘water monsters’ as such. Maybe the water is just inevitable? ( I guess we’ll just wait and see if the seventh movie does anything with this?)

Though this does give me an idea. Where are the killer bird movies? There’s The Birds (1963) which I think suffered from some of the same problems as Night of the Lepus, though not as bad. The Giant Claw (1957) is laughable. We need a movie with giant mutant…petrels or cassowaries or something. Or someone could just make a horror movie with accurate, feathered raptors. Personally, I think they would do well combined with some terrifyingly steep mountain-top terrain, ominous winding caves, and the color scheme/appearance of the lammergeier. Also known as bearded vultures, their diet consists mainly of bone marrow, how cool is that?

______________________________________________________________________

- All birds are dinosaurs, but not all dinosaurs are birds. Just like all mammals are reptiles, but not all reptiles are mammals. Because when we say ‘dinosaur’ or ‘reptile’ we really mean ‘non-avian dinosaur’ or ‘non-mammalian, non-avian reptile’, these groups are paraphyletic, a monophyletic group (descended from a common ancestor) with a few clades excluded.

- In a fun turn of events, a recently described additional specimen of Archaeopteryx, the first bird found to mix dinosaur and bird traits, was found to have hyper-extendable second toes! Little ‘terrible claws’ just like the dromaeosaurs (“The tenth skeletal specimen of Archaeopteryx” Mayr, Pohl, Hartman, Peters, 2007).

- For more info on the evolution of feathers and their relationships to hair and scales see: “The Evolutionary Origin and Diversification of Feathers” Prum, Brush, 2002 and “The anatomical placode in reptile scale morphogenesis indicates shared ancestry among skin appendages in amniotes” Di-Poi, Milinkovitch, 2016

- Zhang, F., Kearns, S., Orr, P. et al. Fossilized melanosomes and the colour of Cretaceous dinosaurs and birds. Nature 463, 1075–1078 (2010).

Leave a comment